Author: Kim Zumach

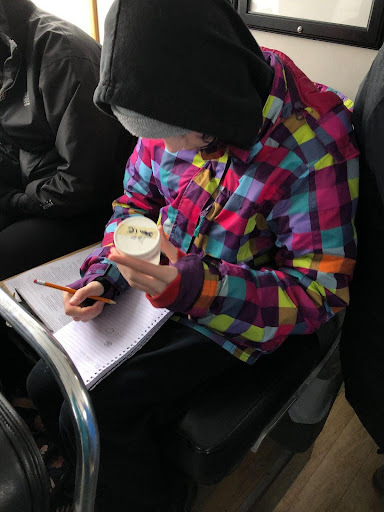

Kim Zumach is a mother, teacher, ocean advocate and nature-nerd. She lives, learns and teaches on the beautiful territory of the Ligwilda'xw Peoples in Campbell River, British Columbia. When not in the classroom teaching eighth graders, she can be found exploring on and around Vancouver Island by kayak, paddleboard, hiking boots or mountain bike. Kim is constantly inspired by the natural world and loves adventuring to new places with her two children, husband and dog.