Looking out over the ocean, often the only sound we hear from the water comes from waves crashing. Sounds produced below the waves bounce off the surface; the boundary between water and air. And our ears are made for hearing in air – underwater sounds are muted, and our vocal cords are made to produce vibrations in air. Sound in water is foreign to most of the human experience.

However, sound is how we study and work to protect marine animals. We listen with a microphone made for use in water, called a hydrophone. Hydrophones can be put in one place (moored) or attached to ocean gliders that travel thousands of kilometres through the water. Hydrophone data can tell us where whales are and when they migrate to different regions, and also about their behaviours, based not only on the presence of whale calls, but on the type.

Sound travels quickly and unimpeded over immense distances in the ocean. In comparison, sunlight bounces off of water molecules and eventually dissipates – the ocean is on average about 4 km deep, yet sunlight only reaches the first few hundred metres. As a result, ocean life has evolved ways to use sound instead of light. In an article for the BBC, whale researcher Christopher Clark said, “A whale's consciousness and sense of self is based on sound, not sight.” For whales, even in the absence of light, there is still sight.

In fact, whales call to one another when close by, but also over hundreds of kilometres, sometimes never to meet. Like making a long distance phone call; as Michelle Fournet, a humpback communication researcher put it, the whales call back and forth from huge distances as though to say, ‘‘I am here and there you are.’

Although recording whale and other marine mammal sounds date back to the 1960s, it’s only in about the last decade that we’ve learned how much sound is used by all kinds of ocean dwellers. For marine animals, the ocean is a noisy place.

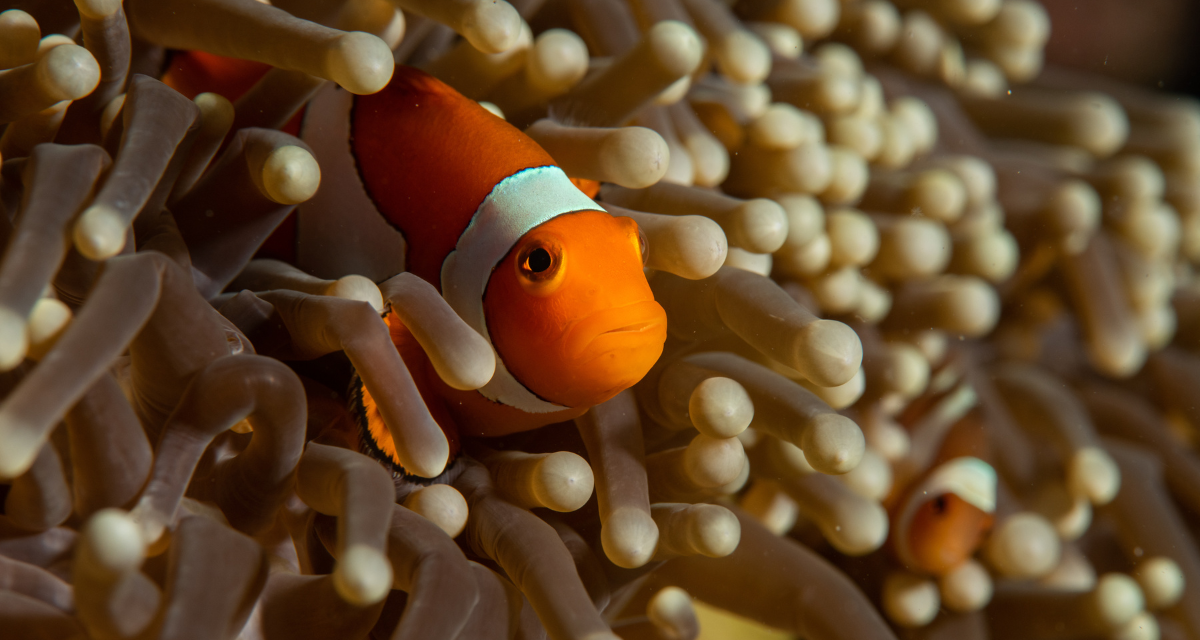

A great example is boisterous coral reefs. After they hatch on coral reefs, many fish fry move with currents into the open ocean, and once mature, look for a home. And those fish find their way home, back to the coral reefs, by sound. They are drawn by the cacophony of the reef’s inhabitants going about their lives. In fact, researchers have found that by playing the sounds made by healthy reefs, they can draw fish to degraded reefs, where the fish settle and begin to rebuild the reef’s community.

Listening to coral reefs, researchers are still identifying what animal is responsible for each of the many and diverse noises. Clown fish in their anemone, for example, make a clacking sound to communicate with their family by banging their teeth together. And a small yellow fish called an ambon damselfish makes a high pitched whooping sound as it defends its eggs.